First Course Design Decisions

In this initial phase you consider:

- Your Situational Factors

- Chunk the course into 4-7 modules

- Identify aims of your modules

- Begin imaging 4S kinds of questions to organize the content

- Develop learning outcomes

Read before you get started

- Wiggins and McTighe’s Why Backwards Design is Best

- Roadmap to Creating a TBL module

Chunking your Course into Modules

To start with, first you need to chunk your course into 4-7 chunks. Each piece is usually about 2-3 weeks or 6-10 hours of class time. If you rely on how textbooks are typically organized you might have some trouble imagining only 4-7 chunks. Often textbooks are series of topics that almost implicitly want you to lecture 1 a week…we a can fall into this trap because we want to be sure that all the content is covered. But TBL is different. To design a TBL course I would suggest looking at the course topics and trying to come up with alternative organizational schemes or metaphors. Maybe you can build the course around some interesting essential questions.

For example, in a Materials Engineering course, if I was to follow most textbooks…we would introduce one atom, then two atoms, then molecules and crystals, finally different materials and equations to calculate their properties….I’m already bored….how about we build the course differently around just two questions…why do things fail? And how do we pick the “right” material for the job? When we reorganizing the course around some interesting, concrete questions, ideas for learning activities start to almost automatically come to mind.

Mapping out the Pieces

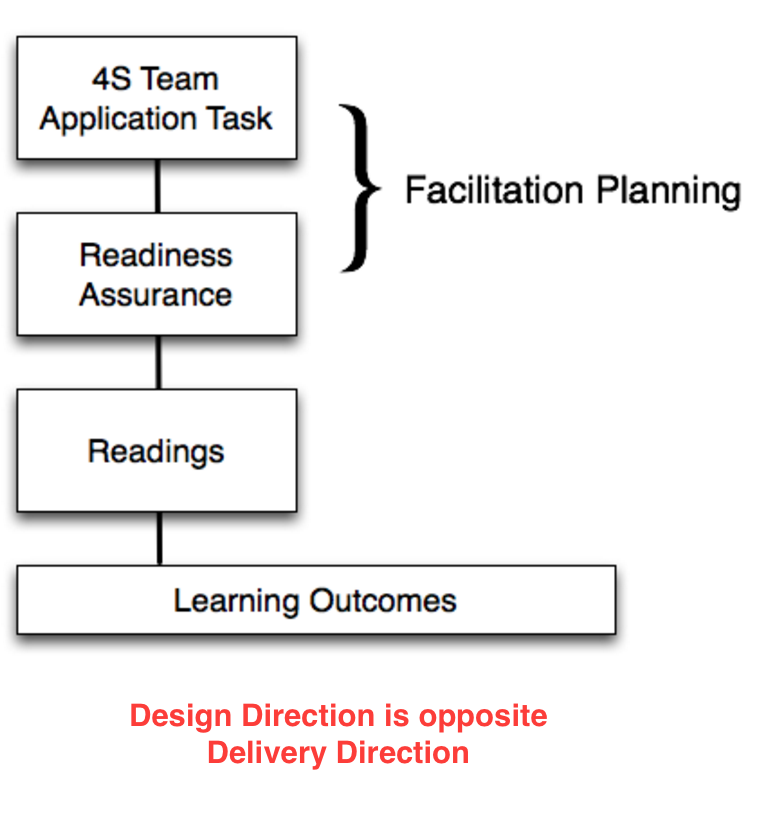

The typical 2-week TBL module start with students completing assigned pre-readings or other preparation materials, and then at the first class meeting they complete the Readiness Assurance Process (multiple choice test). By the end of the Readiness Assurance Process we have some “assurance” that your students have the required minimum foundational knowledge to begin problem solving.

The rest of the module focuses on having students use the course concepts to solve problems structured using TBL’s 4S framework. During the problem-solving process the instructors will sometimes provide very short mini-lectures/expert clarifications when teams are having difficulty progressing.

The module ends with a short instructor-led review of all that has been learned. TBL modules always have the same progression of activities – student pre-class preparation, Readiness Assurance Process, and 4S team tasks.

Imagining Culminating Student Performance

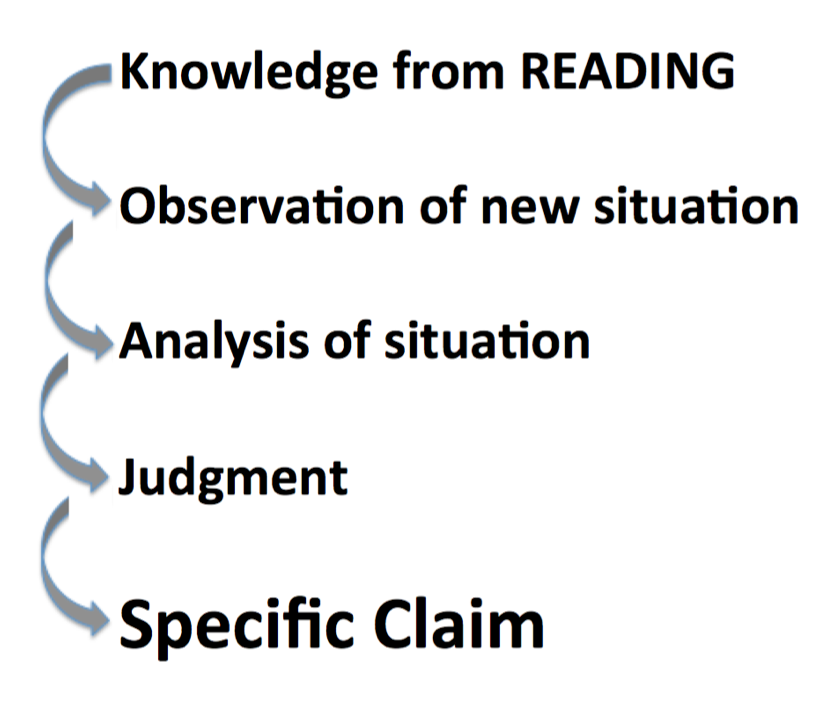

The ultimate goal of any TBL course is helping students learn how to apply course concepts to solve interesting problems. TBL uses the very specific 4S framework to structure the problems to ensure that students do deep analysis, make difficult judgments and decisions, build justifications and arguments that can withstand the scrutiny of other teams during the discussion following the public simultaneous report.

Great 4S tasks focus on the concrete application of abstract understandings from the readings. You are looking for those kinds of analysis and decisions that experts in your field are routinely asked to make.

During a 4S Application task, students get to concretely apply what they have abstractly learned from the readings. Because of the abstract nature of understanding, it is not “teachable” in the conventional sense. An understanding can be gained only through guided inference whereby the learner is helped to make, recognize, or verify a conclusion. (Wiggins and McTighe, 2013). You want students connecting abstract concepts from the readings with concrete experience during the 4S team Application tasks. Making connections during 4S team tasks is important to consolidate student learning. Helping students see gaps in their knowledge motivates the students’ look up what they don’t know and then immediately putting that knowledge into action tests and deepens their understanding. You need to present a scenario that creates the context in which what students “know” abstractly (via their readings) is put to the test when they try to “use” it in concrete, specific case. Your job is to find or, if necessary, fabricate these scenarios.

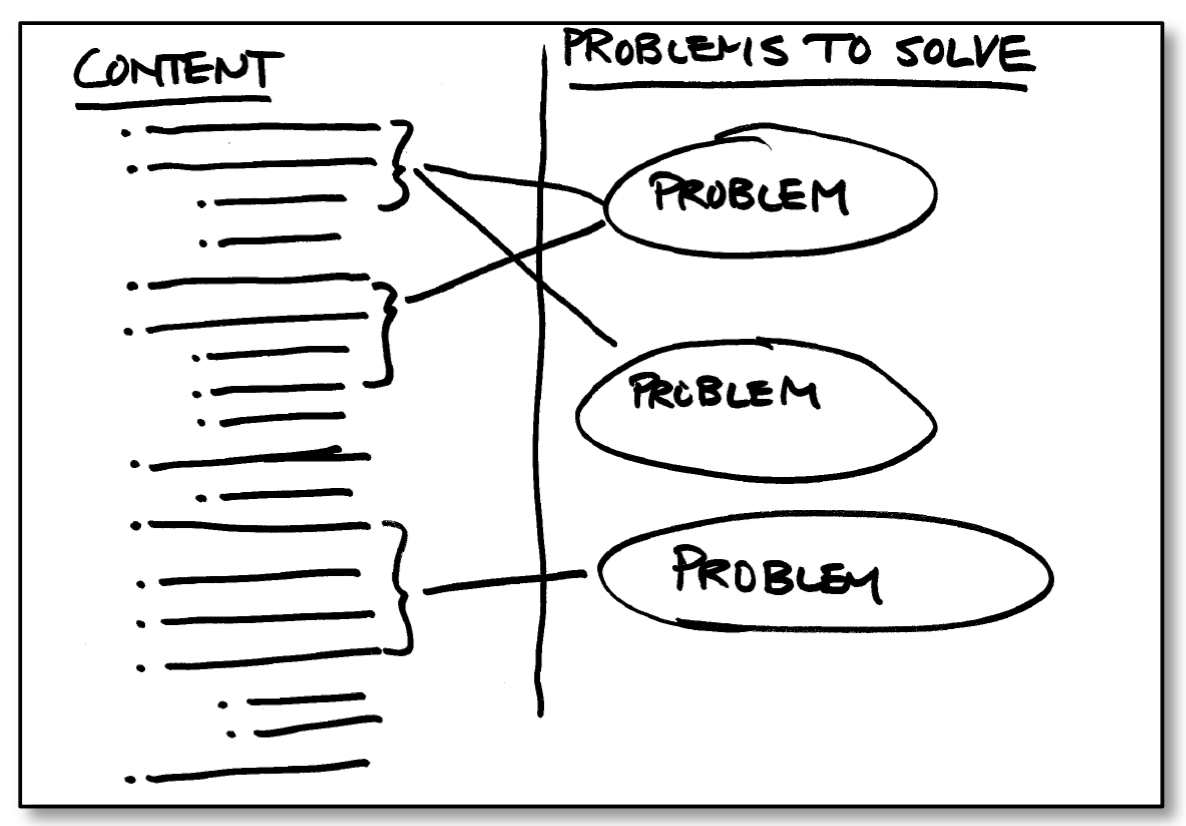

Brainstorming what I want students to be able to do” and those concrete disciplinary actions and relating it to the “content I feel compelled to cover” can be difficult and get you stuck – how do you get unstuck?

Take a ledger size page and divide it into two quadrants. Down the right side brainstorm for ideas what you would like your students to be able to do/solve. Down the left side, list all the content you feel compelled to cover in your course. What you are hoping to find are compelling problems to solve, that lead back to the content you hope to cover – this is an iterative process of focusing the problems, considering what content is really essential or what content might need to be added to allow the students to successfully solve the problems.

Hopefully significant, interesting discipline specific concrete actions emerge that will become the focus for the development of your application activities.

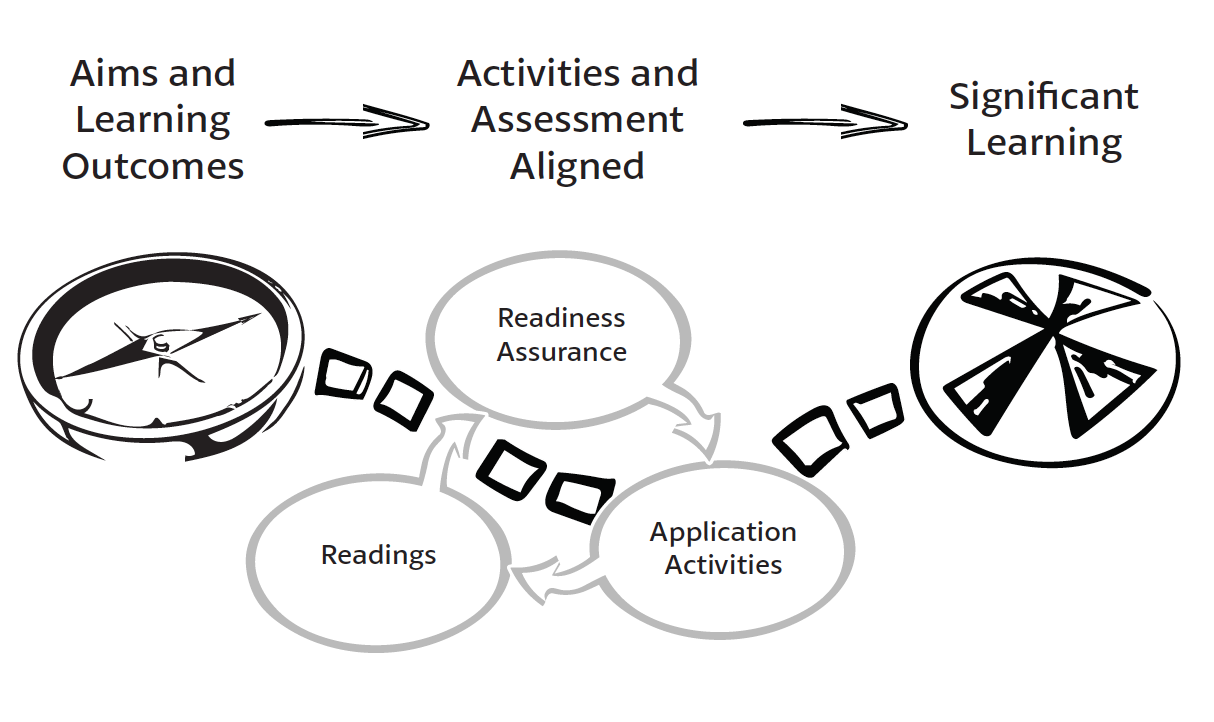

Writing Aims and Learning Outcomes

First, you need to develop your Instructional Aims. Aims are your general instructional intentions for the module. Aims are always written from the point of view of the teacher, the things you hope to achieve as a teacher.

Next, you develop Learning Outcomes. Learning Outcomes focus directly on the students and get more detailed on exactly what the students will be able to do by module end. Learning Outcomes often contain references to the knowledge, skills, and judgement abilities you want your students to develop. These Learning Outcome statements are often the precursors to ideas for 4S Application tasks. When we start thinking about the 4S Application tasks, we want to try to write Learning Outcomes that focus on more concrete actions rather than abstract understanding. We are looking for concrete actions just like a discipline expert takes. Good Learning Outcomes express how experts in your field or discipline would use the course content to solve disciplinary problems. The more concrete you can make the learning outcomes the easier it will be to develop 4S Application tasks from them.

Note below how concrete, active Learning Outcomes use verbs that are already the seeds for 4S Application task development!

Sample Learning Outcomes for a statistic course: by the end of this course students will be able to use their knowledge of statistical principles to:

- Complete a statistical analysis

- Select an appropriate sampling plan

- Develop a survey instrument and plan to gather information from a specific population

Sample Learning Outcomes for a genetics counselling course: by the end of this course students will be able to use their knowledge of genomics to:

- Interpret genome sequencing data

- Identify genetic markers with greatest risk of disease/abnormality

- Develop counselling plan to work with specific family issues

Sample Learning Outcomes for a business course: by the end of this course students will be able to use their knowledge of marketing principles to…

- Conduct a market analyses

- Evaluate a marketing plan

- Select or Develop marketing techniques to reach specific populations of clients

Sample Learning Outcomes for a history course: by the end of this course students will be able to use their knowledge of early Canadian history to…

- Interpret written accounts of historical events in light of cultural dynamics

- Assess (and estimate) the bias or orientation of a given author

- Develop arguments for current policies or political positions based on historical context